Fusion in American history

Fusion voting was a central part of American politics for the first 125 years of the country’s history. In the 1820s, it was used by an early labor party — the Workingmen’s Party of Philadelphia — in elections for the Philadelphia Council. They fused with the Jacksonian Democrats, but asked voters to support the Workingmen’s Party by voting their ticket as a way to show support for the 10-hour workday.

How Fusion enabled the abolition movement

Starting in the 1840’s and early 1850s, fusion voting really demonstrated its usefulness as a way for important, dissident views to enter the public discourse. Both major parties, the Whigs and the Democrats, had anti-slavery factions, but the parties strove mightily to keep these sectional tensions submerged in favor of party unity.

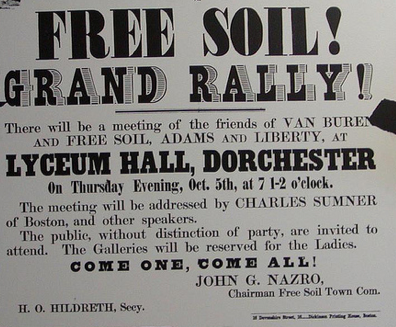

Anti-slavery forces chose not to stay submerged. So-called “political” abolitionists formed new parties — the Liberty Party, Anti-Nebraska Party, Free Soil Party. Each of these were assemblages of citizens (what a party is) who needed to build an identity and an organization in order to influence the political process. They used fusion to make their opposition to the “Slave Power” more electorally visible.

These new parties’ leaders and voters were of course mostly white people, but in some states they included free Black men. They often ran stand-alone candidates for office, but they also looked for favorable strategic opportunities to identify, elevate and “fuse” with anti-Slavery politicians – mostly Whigs but some Democrats, sometimes branded as “Independent Democrats” — as a way to force abolition onto the national agenda. Perhaps the most famous example of the power of fusion was the election of Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner, who was elected in 1850 by a fusion of Free Soil and Whig votes.

Eventually the Whigs collapsed due to internal tensions on slavery. A new minor party called the “Republican Party” filled the vacuum created by that collapse with the various fusion parties merging into a force capable of winning elections in the northern states beginning in 1855. By 1860, this new party has elected a president, and the Republican Party replaced the Whigs as America’s other major party.

Fusion after the Civil War: a force for economic and racial justice

After the Civil War, fusion balloting continued as a central feature of American democracy. Minor parties – Greenback, Labor, Silver, People’s, Suffragist, Temperance – each wanted to put its views forward, and they were able to do so because ours was a multiparty democracy. In most states, minor parties thrived and played a major role in the debates of the time. There were even a few states where fusion permitted an astounding electoral alliance to emerge, an alliance between the white yeoman farmers who voted Populist and the newly enfranchised Black men who voted Republican. They differed culturally but they were united politically, especially in the Readjusters Party of Virginia and under the Fusionism banner in North Carolina.

This bi-racial, class-conscious unity became the object of white supremacist anger generally and Klan terror specifically. These alliances and the very ideal of a mutli-racial social democracy could not survive. Jim Crow Democrats began their nearly century-long rule, and no one should be surprised that among the early laws they passed was one to ensure that another multi-racial, class-conscious electoral alliance did not materialize again. Starting in the late 1890s, as states took on the job of printing ballots and determining the rules for ballot access, they banned fusion as a way to keep such alliances from being viable.

Fusion was also banned in the North by Republicans who were being challenged by the political alliance of Populists and Democrats, the so-called “Farmer-Worker” alliance of the 1880’s and 1890’s. It’s a different story than in the South, but the basics are the same: fusion enabled coalitions that challenged the dominant power, and the dominant power responded by changing the rules to preclude any such coalitions.