FAQs

-

Fusion voting allows a candidate for public office to be nominated by more than one party in a given race – with two or more parties “fusing” on a single candidate – and in doing so, allow new voices, new ideas, and new parties to emerge.

The votes for a candidate under a new party banner count the same as those on the major party line, but it’s a way for the new party to gain and demonstrate support amongst the public while backing a candidate with a real shot of winning. And it’s a way for voters to send a signal – without spoiling an election or wasting one’s vote – to the candidate and to the major parties to pay attention to that third party’s platform and priorities.

-

Whatever one’s feelings may be about a particular political party, parties are critical to a functioning democracy: most people are too busy to research every candidate, so parties help individuals vote efficiently and engage in politics. (When a consumer lacks expertise around electronics, for example, a brand can help that consumer purchase a product that the consumer can likely rely upon. The same is true in politics. A voter may not have detailed information about every candidate, but a candidate’s party brand signals to the voter what a candidate is likely to stand for.)

But the two major parties aren’t incentivized to reduce extreme polarization. Instead, primaries, gerrymandering, geographic self-sorting, and news and social media bubbles keep us locked in partisan warfare.

The system won’t self-correct by exhorting politicians to be more reasonable or to listen to the other side. Change will only come if the rules are rewritten to incentivize cooperation and compromise. Fusion voting would help change those rules and incentives (See How would fusion parties influence major parties?, below), while also supporting the growth of political parties, which are the backbone of a healthy democracy.

-

Reinstating fusion voting is a common sense solution to counter the extremism and polarization ingrained in our political system. Fusion voting benefits:

- Voters: Fusion voting gives voters the ability to vote for a major party candidate with a real shot of winning on a party line that best matches their values. The voter neither “wastes” their vote on a new party candidate who has no chance of winning, nor “spoils” the election by unintentionally helping the major party candidate they least prefer. Fusion also allows voters to vote for a major party candidate they like, without having to signal support for a major party they don’t support.

- New Parties: Fusion voting gives new parties more influence over the political agenda by incentivizing major party candidates to appeal to the voters represented by that new party.

Candidates: Fusion voting produces more votes for major party candidates who appeal to multiple constituencies and are thus able to secure additional party endorsements.

-

Fusion voting is still alive and well in Connecticut and New York, but it was outlawed in most states in the early 1900s because it worked as intended to create more parties that were able to exert influence on the major parties. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, smaller and emerging party voters consistently leveraged fusion voting to advance their agendas. The two major parties banned fusion in order to stamp out competition and consolidate their power. Most legal scholars believe this was, and is, an unconstitutional limit on the freedoms of association and assembly that all citizens should enjoy. The fusion ban has made it nearly impossible for new voices and parties to exercise real power and influence over the political agenda. This in turn has helped cement the dysfunctional, zero-sum nature of the two-party system and the dysfunctional government that it produces.

-

We believe that the conditions are ripe for our effort. Americans are hungry for more choices on the ballot and there is widespread dissatisfaction with the two-party system. Many states have constitutions that offer robust support for their citizens’ rights of free speech and association, which portend well for lawsuits like the one brought by the Moderate Party of New Jersey. And as the two-party doom loop worsens, we believe the prospects for electoral reforms like fusion can only improve.

-

In this moment, the most likely outcome would be the birth of centrist parties that support democracy, compromise and the rule of law, appealing to center-right and center-left constituencies. This party would give voters tired of partisan warfare a place to go, and would influence the two major parties to move away from the extremes and towards moderation. In the longer term, a limited number of other parties representing various viewpoints across the political spectrum would also emerge, enriching the political discourse beyond just red and blue. For example, in New York State (traditionally led by moderates from both parties), fusion voting has produced durable and constructive minor parties, like the Conservative Party on the right and Working Families Party on the left.

-

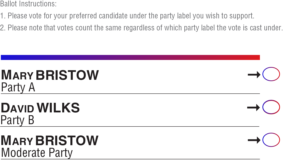

Fusion voting is a practice in which a candidate can appear on the ballot as the nominee of more than one party. On a single ballot, one person can be the candidate for both a major and a minor party. In close races, the votes cast for a candidate under a minor party can tip the scales, as this demonstrates a wide range of appeal. Here is a fictional sample ballot:

-

If votes go to a fusion party, candidates and parties would take note. They’d adjust to capture those votes. With both major parties winning power by small margins, the fusion party could potentially have significant influence.

Imagine a “center” party that does not run its own slate of candidates, but like all fusion parties reviews the records of the two major party candidates and nominates the one with the clearest commitment to cross-partisan cooperation, problem solving, and the rule of law. It wouldn’t take long for the nomination of this center party to be an important, even decisive, factor in many elections. This, in turn, could encourage more compromise and productivity in policy making as the major parties compete for those voters.

We’ve seen this influence happen throughout history too. For example, the Workingmen’s Party of the 1820s and the abolitionist Liberty, Barnburners, and Free Soil parties of the 1840s and 1850s all utilized fusion voting to advance their causes and force the major parties to support their agendas. This created a vigorous, multi-party system with more representation of diverse political views and governing reforms that were responsive to the major challenges of the day.

-

A “wasted” vote is one that is cast for a candidate with no chance of winning.

A “spoiler” vote occurs when one votes for a third party candidate with no shot of winning and in doing so siphons away a vote from the major party candidate one likes best. This in turn helps to elect the major party candidate one likes the least.

Third parties face an insuperable obstacle in our system. In non-fusion states (48 of the 50), third party sympathizers are almost always wasting their votes on candidates with no credible chance of winning. In some rare cases, the wasted votes can actually add up to a total that spoils an election. In the last thirty years, two presidential elections were arguably “spoiled.” Ross Perot’s voters inadvertently helped Bill Clinton win, and Ralph Nader’s voters no doubt helped secure George W. Bush’s victory over Al Gore.

-

No. In states like Connecticut and New York where fusion is the norm, there hasn’t been a proliferation of parties. There are two main reasons for this: states still have stringent ballot access requirements for minor parties, and candidates must accept nominations (making it hard for hyper-fringe parties to gain a foothold). Fringe parties don’t typically get many votes, so there is less of an incentive for a politician to want that association.

As fusion voting expands, states will set appropriate thresholds to ensure that minor parties reach clear benchmarks demonstrating public support in order to gain their own ballot line. In practice, states that permit fusion have seen between two and four minor parties compete consistently for votes and no issues with voter confusion.

-

The ability to fuse with or cross-endorse candidates of other parties incentivizes minor parties to seek voter support for leverage with one or both of the major parties. Unlike our current system, which forces minor parties into the unenviable position of having to run candidates who have no chance of winning, and thus can only “spoil” races and waste supporters’ votes, fusion leads to more collaboration between multiple parties in pursuit of common goals.

As for the dangers of extremist parties, our problem today is that in a two-party duopoly, if an extreme faction manages to capture power inside one of those parties, they can exert influence way beyond their actual standing in public opinion. It is possible that people on the left or right will choose to form stand-alone parties, which is their right in a democracy, but they can already do that today. But they will not be able to give their ballot line endorsement to a major party candidate without the candidate’s consent.

In general, fusion encourages groups who currently feel unrepresented by either of the major parties to organize. At present, that describes many people in the political center. In the future, if other groups feel unrepresented, fusion encourages them to organize for leverage within the system. Groups that are shut out of the system for too long become anti-system extremists. Giving voters more voice and representation is a strong anti-extremism reform.

-

Primaries reflect the dominant preference of the voters in a given party. Some moderates in both parties hope that open primaries might reduce extremism, but unfortunately neither the scholarly studies nor the practical experience in the 23 states with open primaries support this contention. For example, 70% of the members (14 of 20) of the anti-democracy Freedom Caucus in the US House were elected from open-primary states, which is not much of an advertisement for its moderating impact.

Political science studies, however, do demonstrate that extremists who win in primaries pay a slight penalty in the general elections. Fusion offers a clear path to increase this penalty for extremism by offering a ballot line in general elections and a powerful organized voice for moderates.

The most reliable way to reduce the power of anti-democracy extremists who succeed in winning primary elections is to have them fail in the subsequent general elections. They need to pay a price for their views, and that can best be accomplished by a new, pro-democracy party of the center, nested in a fusion-legal regime. Whether that new fusion party can play this role will of course depend not only on the re-legalization of fusion, but equally on the skill and determination of state-based leaders and organizers.

-

The greater risk to American democracy is a political system characterized by hyper-polarization, in which the two major parties are each pulled to political extremes and an emerging centrist plurality finds itself homeless, without a political voice. A fusion system, in which minor parties participate in forming political coalitions, was the American tradition until the major parties outlawed it around the turn of the last century.

Legalizing fusion is not meant as a way to make American democracy more European. It is a restoration of a form of American democracy that served us well for our first hundred years, allowing new parties and alliances to form in response to shifting national priorities and injecting more proportionality into our political system, something we badly need more of today. We’ve always made our own way, learned and adapted to grow and prosper. If we don’t do that now, our standing in the world may continue to decline. Political innovation is an American strength.